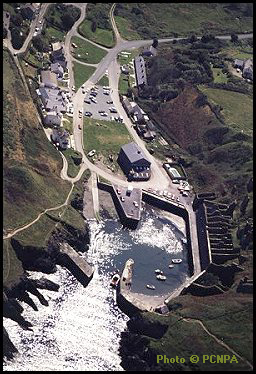

Although it is fairly quiet place today, with only an estimated

100-200 visitors at peak periods, Porthgain has quite a different history.

Like many other harbours around the British Isles, in the 19th

century Porthgain was a hive of activity. At its peak, approximately

100 steam coasters, sloops and ketches worked the port, helping with

the export of stone, slate and bricks.

Although it is fairly quiet place today, with only an estimated

100-200 visitors at peak periods, Porthgain has quite a different history.

Like many other harbours around the British Isles, in the 19th

century Porthgain was a hive of activity. At its peak, approximately

100 steam coasters, sloops and ketches worked the port, helping with

the export of stone, slate and bricks.

At that time something like 40000 tons of stone (granite from quarries near Pen Clegr) used to leave the harbour each year. The best stone was exported for public buildings in London, Liverpool and Dublin. Other stone was crushed in hoppers and sent as roadstone to Bristol and Kent.

Slate, meanwhile, from quarries at Abereiddi, was brought along a tramroad and exported for use mainly as roofing material.

And bricks too were manufactured at Ty Mawr (literally "big house") before shipping. The clay for these was brought in through a specially constructed railway tunnel.

With all this activity, some navigational guidance needed to be given

for sailors

entering the port. The two navigation marks that can be seen today

on the headlands either side of the port were the

way this was achieved. Standing approximately 22 feet high, and

lime-washed white, they stood out from a distance, and the

difference in their shape (one pyramidal and one conical) helped

distinguish the one from the other.

With all this activity, some navigational guidance needed to be given

for sailors

entering the port. The two navigation marks that can be seen today

on the headlands either side of the port were the

way this was achieved. Standing approximately 22 feet high, and

lime-washed white, they stood out from a distance, and the

difference in their shape (one pyramidal and one conical) helped

distinguish the one from the other.

Changing economics of transport meant that Porthgain effectively ceased as a major distribution centre in the early 1930s. The National Park Authority, however, is keen to conserve and restore elements of Porthgain as a tourist attraction. Both the navigation marks and Ty Mawr have recently been restored. Other work carried out includes Porthgain village study and Porthgain harbours and hoppers study, projects part-funded by West Wales Task Force funding.